Photo Credit: Mike Cason, Which counties moved on Alabama’s new congressional district map?, Alabama Media Group (July 22, 2023), https://www.al.com/news/2023/07/zero-for-11-election-results-show-new-alabama-map-wont-fix-voting-rights-violation-black-voters-say.html.

Authored By: John Paradise

The State of Alabama is no stranger to accusations concerning infractions of voting rights. With historical foundations of Jim Crow era laws that hinged voting participation on literacy and property ownership, the implementation and, of higher importance, the desired outcome of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 has proved difficult for the State to achieve.[1] This difficulty can be evidenced by the State of Alabama’s presence in a significant proportion of landmark Supreme Court decisions regarding the interpretation of the Voting Rights Act. It was voting policies in the City of Mobile that garnered the highly criticized and now overruled Supreme Court holding which purported the notion that voting discrimination is only present when a “racially discriminatory motivation” or an “invidious purpose” could be shown.[2] More recently, it was Shelby County, Alabama that successfully sought to have Sections 5 and 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act – both safeguards from counties changing election laws without official authorization from the Attorney General – declared unconstitutional.[3] However, no topic regarding the protection of Alabamian’s voting rights has received public and judicial contention as has the issue of the State’s congressional map.

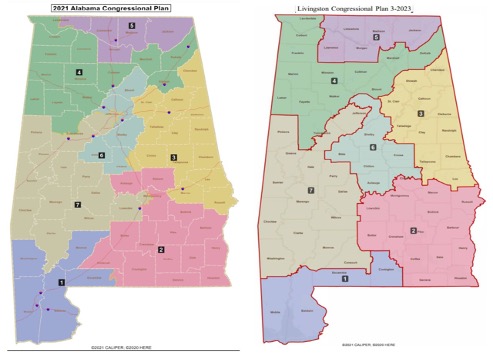

The Alabama congressional map is currently divided into seven districts.[4] Detractors of the congressional voting make-up of the State have long claimed the map is strategically proportioned to limit the voting efficacy of the minority vote, which is synonymous in Alabama with the Black vote.[5] Judicial action regarding the congressional map of Alabama first surfaced in 1992 with a group of plaintiffs representing “all African-American citizens of the State of Alabama.” These plaintiffs claimed that the State’s black population was “sufficiently compact and contiguous” to comprise an African-American majority congressional district.[6] The federal district court obliged, reworking District Seven (7) into an irregularly shaped district that roped off populous clusters of African American voters in the urban centers of Birmingham and Montgomery and connected the two across a swath of majority-black rural area known in Alabama as the “Black Belt.”[7] While this creation has now been held unconstitutional as an “extreme” form of racial gerrymandering, the federal district court’s creation remained relatively unchanged for over thirty years.[8] With eighty percent (80%) of Black Alabamians voting Democratic, the creation of the first-ever majority-Black Alabama district in District 7 appears to have been used as an affront to appease the African American caucus while also strategically lowering the democratic vote in Birmingham and Montgomery – two of Alabama’s largest cities.[9] However, in June 2023, an unsuspected harbinger came in the form of a Supreme Court decision where a historically conservative Court found Alabama’s congressional map to violate the Voting Rights Act.[10] Subsequently, the State was ordered to redraw the districts to allow Black voters to “have an [additional] opportunity to elect a representative of their choice.”[11]

The foundations for Allen v. Milligan began in 2020 when the decennial census revealed that the population of Alabama had increased by 5.1%.[12] While this increase did not warrant a change in the number of seats Alabama would receive in the House, the growth was unevenly portioned and ultimately rendered the current Congressional map, created in 2011, out of date.[13] The updated 2020 map was nearly identical to the previous 2011 map, again reflecting only one district in which Black voters made up the majority voting age population.[14] In response, three groups of plaintiffs sought injunctive relief in federal district court against Alabama’s Secretary of State in an effort to prohibit the use of the 2020 map.[15] In a lengthy 227-page opinion, the federal district court promulgated that the issue of whether the 2020 Alabama congressional map violated the Voting Rights Act was not “a close one,” preliminarily enjoining the State from using it in subsequential elections.[16]

To determine whether the district court correctly interpreted the Voting Rights Act, the Supreme Court granted certiorari of the State’s appeal. When examining whether there has been a Voting Rights infraction regarding congressional districting, the Court has long applied the Gingles framework to given facts.[17] In Gingles, the Supreme Court found that the State of North Carolina unlawfully discriminated against African Americans by diluting their vote through strategic districting.[18] The Court opined that the greatest risk for this occurs when “minority and majority voters consistently prefer different candidates” and where minority voters are zoned in a majority population that “regularly defeats” their choices.[19] To ease the process of determining when this form of voting discrimination is present, the Court further purported three preconditions that the plaintiff must satisfy to successfully bring a Voting Rights action against a state for unlawful congressional districting.[20] These preconditions set forth that the minority group must: (1) be “sufficiently large and geographically compact” to make-up a majority in a “reasonably configured” district; (2) be politically cohesive; and (3) be able to demonstrate that the white majority “votes sufficiently as a bloc,” enabling it to defeat the minority’s choice of candidate.[21] To support the first precondition, the Plaintiffs provided examples of eleven districting maps which not only granted an additional majority-black district to the State, but were also “compact, contained equal populations, [] contiguous, and respected existing political subdivisions.”[22] The Court further claimed that there was “no serious dispute” regarding preconditions two and three for the Gingles framework, with voting demographics revealed that Black voters averagely supported their choice of candidate with 92.3% of the vote, where white voters only voted for Black-preferred candidates 15.4% of the time.[23] With these preconditions satisfied, the Court ruled that under the totality of the circumstances, African American Alabamians were enjoying “virtually zero success in statewide elections.”[24] Accordingly, the Court held that the federal district court did not err in finding that the current Alabama congressional map violated the Voting Rights Act and could not constitutionally be enforced.[25]

In affirming the district court’s holding, the Supreme Court has required the State to create a new congressional map with a second majority Black district or “something quite close to it” in order to afford Black voters an opportunity to elect a candidate of their choice.[26] Having released such opinion on June 8, 2023, the Supreme Court tasked the Alabama Legislature to have a map meeting these requirements approved by July, 21, 2023.[27] Sparing little time, the State Legislature approved a new map on the day of the deadline; however, it appears evident that the new map fails to meet the guidelines required of it by the Court.[28] The resulting map does not add a second majority-Black district; instead, it increases the Black voting age population in District 2 and covers southeast Alabama from 30% to 42.5%.[29] In hopes that the rezoning of District 2 would be the second “opportunity” district for Black Voters, the democratic caucus of Alabama has judicially challenged the implementation of the redrawn map.[30] With the redrawn District, demographics reveal that the Black-preferred candidate received less votes than the white-preferred counterpart in all head-to-head elections since 2014 by an average deficit of more than ten percentage points.[31] Thus, with Black voters in the newly configured District 2 being unable to elect their preferred candidates, detractors claim that the new map approved by the Legislature offers no more opportunity than it did with the old map, therefore categorizing it as unlawful under the Supreme Court’s guidelines.[32]

A three-judge federal district court panel is scheduled to hear the objections to the new map on August 14, 2023.[33] Alabama’s Secretary of State has ordered a new map to be prepared within conformity to the Supreme Court’s guidelines by October 1.[34] The expectations of the new map suggest that a third-party special master will be appointed by the court to redraw the congressional map if the district court finds the Legislature’s approved map invalid.[35] However, there is currently an in-party split within the Alabama democratic caucus regarding which map should be adopted by the federal court.[36] By keeping a part of Jefferson County connected to the already majority-Black District 7, some Alabama democrats suggest the only way to amend the State’s voting infractions is to create a second majority-Black district in the eastern half of Alabama’s “Black Belt.”[37] While this would no doubt satisfy the Supreme Court’s demands, others suggest a different and more logical way to create a second opportunity district for Black Alabamians.[38] Viewing the irrationality of the make-up of District 7 – which connects Birmingham (Jefferson County), the largest urban metropolitan area in the State, to the more southern, rural area of the western half of the “Black Belt” – some believe the resolution lies in making Jefferson County the entirety of the 6th congressional district.[39] But, with 40% of Jefferson County being African American, this would not create a second majority-Black district.[40] However, voting demographics in Jefferson County reveal that opportunity is created by the fact that the Black-preferred candidate has received more votes than their Republican opponents in a significant majority of elections held since 2012.[41] This opportunity derives from Jefferson County having more white voters who support Democrats than other portions of the State.[42]

While it is unclear which route is more efficient in further amending the century long voting rights disparity in Alabama, it appears transparent why Alabama Republicans are dragging their feet with the demands of the Supreme Court. United States House Republicans hold just a narrow edge over Democrats, with 222 seats belonging to the GOP and 212 being attributed to their democratic counterpart.[43] Thus, with such a close margin of difference in House control, the majority Republican Alabama Legislature’s response to the Supreme Court’s decision in Allen v. Milligan appears to be an attempt maintain national political influence.[44] In defending the map created by the State Legislature, Alabama Republican’s state that the new district map complies with the Court’s orders because “it increases Black influence.”[45] However, “influence” is not synonymous with “opportunity,” and certain topics are more important than political absolutism. Voting equality amongst all citizens, along with full and accurate political representation, should be classified as one of these topics. Historically, the State of Alabama has chosen the political absolutist option; beginning with the Jim Crow era up to the three decades of implementing a congressional map labeled an “extreme” form of racial gerrymandering. As the district court adjourns on August 14 to determine the future of Alabama’s congressional map, an opportunity has been presented to the State to do what is right and take the first step in a rewrite of historical precedent. Hopefully, fairness will prevail.

1 Christopher Maloney, Voting Rights Act of 1965 in Alabama, Encyclopedia of Alabama (Jul. 2, 2020), https://encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/voting-rights-act-of-1965-in-alabama/.

[2] City of Mobile, Alabama. v. Bolden, 100 S.Ct. 1490, 1497 (1980).

[3] Shelby County., Alabama v. Holder, 133 S.Ct. 2612, 2631 (2013).

[4] State District Maps, Ala. Sec’y of State (last visited Aug. 2, 2023), https://www.sos.alabama.gov/alabama-votes/state-district-maps.

[5] Party Affiliation Among Adults in Alabama by Race/Ethnicity, PEW Rsch. Ctr., https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/religious-landscape-study/compare/party-affiliation/by/racial-and-ethnic-composition/among/state/alabama/ (last visited Aug. 2, 2023).

[6] Wesch v. Hunt, 785 F. Supp. 1491, 1498 (S.D. Ala. 1992).

[7] Id. at 1499; Allen v. Milligan, 143 S.Ct. 1487, 1542 (2023).

[8] Allen, 143 S.Ct. at 1542.

[9] Ala. Sec’y of State, supra note 5.

[10] Allen, 143 S.Ct. at 1501.

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] Id. at 1502.

[15] Id. (explaining that the three groups of plaintiffs include: (1) Dr. Marcus Caster; (2) Evan Milligan; and (3) the Singleton plaintiffs).

[16] Id.

[17] Id. at 1493.

[18] Thornburg v. Gingles, 106 S.Ct. 2752, 2765 (1986).

[19] Id.

[20] Id. at 2766; Allen, 143 S.Ct. at 1493.

[21] Allen, 143 S.Ct. at 1493.

[22] Id. at 1504.

[23] Id. at 1505-06.

[24] Id. at 1506.

[25] Id. at 1506.

[26] Id. at 1535.

[27] Mike Cason, Supreme Court Rules Alabama Congressional Map Most Likely Violates Voting Rights Act, AL.com (June 08, 2023), https://www.al.com/news/2023/06/supreme-court-may-rule-today-whether-alabama-congressional-map-violates-voting-rights-act.html.

[28] Mike Cason, Zero for 11: Election Results Show New Alabama Map Won’t Fix Voting Rights Violation, Black Voters Say, AL.com (July 31, 2023), https://www.al.com/news/2023/07/zero-for-11-election-results-show-new-alabama-map-wont-fix-voting-rights-violation-black-voters-say.html.

[29] Mike Cason, GOP Lawmakers Pass Alabama Congressional Map; Democrats Say it Defies Supreme Court, AL.com (July 22, 2023), https://www.al.com/news/2023/07/gop-lawmakers-reach-compromise-on-alabama-congressional-map-democrats-say-it-defies-supreme-court.html.

[30] Mike Cason, Could Democrats Win in Alabama Congressional District That is 40% Black?, AL.com (July 18, 2023), https://www.al.com/news/2023/07/could-democrats-win-in-alabama-congressional-district-that-is-40-black.html.

[31] Cason, supra note 25.

[32] Id.

[33] Cason, supra note 27.

[34] Id.

[35] Id.

[36] Jemma Stephenson, Proposed Alabama Congressional Map Would Only Have 1 Majority-Black District, BirminghamWatch (July 18, 2023), https://birminghamwatch.org/proposed-alabama-congressional-map-would-only-have-1-majority-black-district/.

[37] Id.

[38] Id.

[39] Id.

[40] Cason, supra note 27.

[41] Id.

[42] Id.

[43] Fredreka Schouten, Plaintiffs in High-Profile Redistricting Case Urge Judges to Toss Out Alabama’s Controversial Congressional Map, CNN (July 29, 2023), https://www.cnn.com/2023/07/29/politics/alabama-redistricting-case-congressional-map/index.html.

[44] Brie Stimson, Alabama Lawmakers Reject 2nd Black Majority Congressional District, Increase to 40% After Supreme Court Ruling, Fox News (July 21, 2023), https://www.foxnews.com/politics/alabama-lawmakers-reject-2nd-black-majority-congressional-district-increase-to-40-after-supreme-court-ruling.

[45] Id.