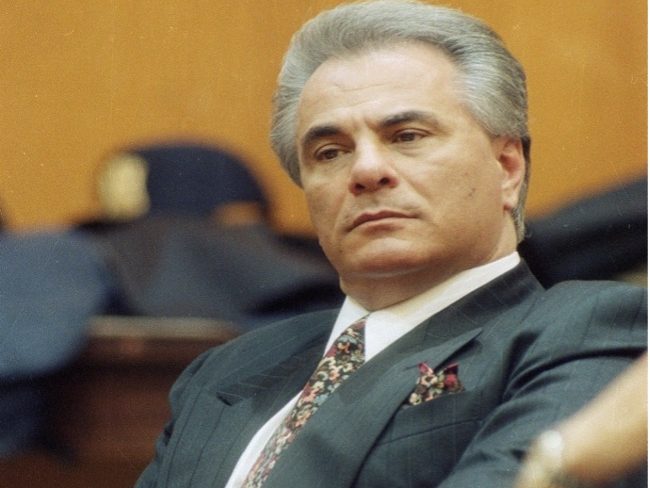

Photo Credit: Associated Press, Photograph of John Gotti Senior, in Charlie Parker, Son of One of America’s Most Feared Mob Bosses John Gotti Reveals What His Childhood Was like in a Mafia Family, The Sun, (Apr. 16, 2019), https://www.thesun.co.uk/sun-men/8869276/son-mob-boss-john-gotti-childhood-mafia-family/.

Authored By: W. Chase Harvey

The Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (“RICO”) is a federal law that was enacted in 1970 to combat organized crime.[1] The law provides extended criminal penalties and civil liabilities for activities which are considered part of an ongoing criminal enterprise.[2] The RICO Act is often implemented to prosecute individuals and groups who are involved in organized crimes.[3] To convict a criminal defendant under federal RICO charges, the government must prove beyond a reasonable doubt:

(1) that an enterprise existed; (2) that the enterprise affected interstate commerce; (3) that the defendant was associated with or employed by the enterprise; (4) that the defendant engaged in a pattern of racketeering activity; and (5) that the defendant conducted or participated in the conduct of the enterprise through that pattern of racketeering activity through the commission of at least two acts of racketeering activity as set forth in the indictment.[4]

Since the rise and fall of the last notorious mob boss, John Gotti (also referred to as “Teflon Don”), federal prosecutors have used the RICO statute to induce fear of lengthy incarceration upon defendants in hopes of getting plea bargains.[5] This saves the federal government time and money, and ultimately ensures a conviction.[6] Because RICO allows for more lenient standards when offering evidence, defendants and their attorneys are often forced to take the negotiated plea deal instead of risking twenty (or more) years in federal prison.[7] These statistics are supported by the Pew Research Center, which found that nearly 98% of federal criminal cases ended before going to trial.[8]

Supporters of RICO argue the law is necessary to combat organized crime and has been a successful tool in bringing down criminal enterprises.[9] They point to high-profile cases where RICO was used to prosecute individuals involved in organized crimes – especially highlighting cases involving the mafia and drug cartels.[10] While such cases are certainly relevant, the mob no longer exists as it once did and now has minimal influence compared to the 1980’s and prior.[11]

Abolitionists of RICO point out several concerns.[12] First, they argue that the law is overly broad and can be applied to individuals who are not involved in organized crime.[13] Critics say that the law’s definition of “racketeering activity” is too vague and can be interpreted in ways the original drafters of the law did not intend.[14] Critics are undoubtedly right when arguing that RICO covers too many crimes.[15] For instance, RICO sets forth penalties for “any act or threat involving murder, kidnapping, gambling, arson, robbery, bribery, extortion, dealing in obscene matter, or dealing in a controlled substance.”[16]The Act also addresses the consequences of running an illegal gambling book.[17] Essentially, every crime under the sun may constitute a RICO violation if the prosecution can sufficiently show a pattern of racketeering activity.[18]

Interestingly, Congress numerically identified that two or more instances of racketeering will constitute a “pattern.”[19] However, any ordinary person outside the legal field will tell you that a pattern is not reduced to simply two instances. For example, Black’s Law Dictionary defines a “pattern” as “[a] mode of behavior or series of acts that are recognizably consistent.”[20] Furthermore, proponents of RICO tend to focus on the high-profile convictions rather than Congress’s initial intent when enacting the Act.[21] When it boils down, Congress passed RICO with intentions to eliminate the mob.[22] But, prosecutors today use RICO to extend criminal sentences for defendants who are clearly not mob bosses.[23]

Opponents of RICO further argue that the law violates due process by allowing prosecutors to bring charges against an individual for crimes that they did not commit directly, but for crimes that were committed by others within the individual’s organization.[24] The opponents argue that this violates the principle of individual culpability and may lead to guilt by association.[25] Finally, some critics argue that RICO has been used to target businesses and individuals who are not involved in organized crime.[26] Such critics argue that the law’s wide-ranging powers have been abused by prosecutors and law enforcement agencies, leading to unjust prosecutions and overly harsh sentences.[27]

Accordingly, the debate over whether RICO should be abolished is complex and multifaceted. While some argue that the law is overly broad and can be abused, others argue it is necessary to combat organized crime.[28] Ultimately, the decision on whether to abolish RICO will depend on how individuals view the role of the law in fighting against crimes and protecting individual rights.

[1] See 18 U.S.C. §§ 1961–68.

[2] U.S. Sent’g Comm’n, Primer: RICO Guideline (Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations), (2020), https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/training/primers/2020_Primer_RICO.pdf.

[3] Stacy M. Brown, Experts Say Lawmakers Should Abolish RICO Law, The Seattle Medium (Oct. 21, 2021), https://seattlemedium.com/experts-say-lawmakers-should-abolish-rico-law/.

[4] U.S. Dep’t of Just. Archives, Just. Manual, Crim. Res. Manual § 109 (2020).

[5] Brown, supra note 3.

[6] Carrie Johnson, The Vast Majority of Criminal Cases End in Plea Bargains, A New Report Finds, NPR (Feb. 22, 2023), https://www.npr.org/2023/02/22/1158356619/plea-bargains-criminal-cases-justice.

[7] Brown, supra note 3(explaining that RICO charges may be added to a conviction involving the same crime that extends a defendant’s sentence by 20 years, or perhaps life).

[8] John Gramlich, Only 2% of Federal Criminal Defendants Went to Trial in 2018, and Most Who Did Were Found Guilty, Pew Research Center (June 11, 2019), https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/11/only-2-of-federal-criminal-defendants-go-to-trial-and-most-who-do-are-found-guilty/.

[9] See Scot J. Paltrow, Debate Rages Over the Long Arm of RICO, The Los Angeles Times (Aug. 13, 1989), https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1989-08-13-fi-800-story.html.

[10] See id.

[11] Selwyn Raab, A Battered and Ailing Mafia Is Losing Its Grip on America, The New York Times (Oct. 22, 1990), https://www.nytimes.com/1990/10/22/us/a-battered-and-ailing-mafia-is-losing-its-grip-on-america.html.

[12] See Brown, supra note 3; Paltrow, supra note 9.

[13] Brown, supra note 3.

[14] Paltrow, supra note 9.

[15] See id.; 18 U.S.C. § 1961 (defining the term known as “racketeering activity”).

[16] 18 U.S.C. § 1961.

[17] See U.S. Atty’s Office, FBI Archives, Phila. Div. (Aug. 8, 2012), https://archives.fbi.gov/archives/philadelphia/press-releases/2012/members-of-alleged-sports-betting-ring-charged-with-racketeering.

[18] See 18 U.S.C. § 1961(5) (defining the phrase “pattern of racketeering activity”).

[19] See id.

[20] Pattern, Black’s Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019).

[21] See Brown, supra note 3; Paltrow, supra note 9.

[22] See Paltrow, supra note 9.

[23] Brown, supra note 3; Eric Levenson & Bill Kirkos, R. Kelly, Already Serving 30 Years for Sex Trafficking, Sentenced to 20 Years in Federal Child Porn Case, CNN (Feb. 23, 2023), https://www.cnn.com/2023/02/23/entertainment/rkelly-chicago-child-porn-sentence/index.html#:~:text=Kelly%2C%2056%2C%20is%20already%20serving,a%20New%20York%20federal%20court; see Aryan Circle Gang Leader Sentenced to Life in Prison for RICO Violations Following HSI Houston-Assisted Investigation, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Sept. 9, 2022), https://www.ice.gov/news/releases/aryan-circle-gang-leader-sentenced-life-prison-rico-violations-following-hsi-houston (noting that the RICO Act has recently been used to disband the Aryan Brotherhood).

[24] George Clemon Freeman, Jr. & Kyle E. McSlarrow, RICO and the Due Process “Void for Vagueness” Test, 45 The Business Lawyer, 1003, 1003 (1990), https://www.jstor.org/stable/40687107; see William L. Anderson & Candice E. Jackson, Law as a Weapon, How RICO Subverts Liberty and the True Purpose of Law, 91 The Independent Review 85, 88 (2004), https://www.independent.org/publications/tir/article.asp?id=215.

[25] See Brown, supra note 3; Anderson & Jackson, supra note 24.

[26] Rob Frehse and Faith Karimi, Some Defendants in College Admission Scam Want Racketeering Charges Dismissed, CNN (Oct. 16, 2019), https://www.cnn.com/2019/10/16/us/college-admission-scandal-racketeering-charges/index.html.

[27] See id.; Anderson & Jackson, supra note 24.

[28] See Brown, supra note 3; Paltrow, supra note 9; Anderson & Jackson, supra note 24.